India’s consumer landscape is one of the most compelling paradoxes of the modern global economy: it offers immense growth potential yet remains unforgiving to brands that assume success can be transplanted from one market to another without deep contextual adaptation. The story of great products falling flat in India is not anecdotal; it is a recurring theme backed by countless industry failures and corroborated in research by consulting firms, market analysts, and consumer behavior specialists. When global brands misread Indian consumers — whether in cultural nuances, taste preferences, pricing expectations, or patterns of product usage — even the most technically superior offerings can fail to generate meaningful consumer pull, leading to stalled sales, poor shelf performance, and eventual exit from one of the world’s fastest-growing markets.

India’s potential has been well documented: a rapidly urbanizing population, rising disposable incomes, and a middle class projected to reach over 580 million people by 2025. Yet beneath these macroeconomic indicators lies a highly segmented market where consumer behavior varies not only by region but also by sociocultural norms and economic strata. Research by the Boston Consulting Group emphasizes that India is not one market but many markets, each with unique preferences in taste, consumption rituals, and value perceptions. The irony for many global brands is that they enter India with a global product playbook — a strategy built on assumptions that worked in homogeneous markets such as Western Europe or North America — and then expect Indian consumers to behave in similar ways. This fundamental misalignment between expectation and reality is the root cause of many high-profile failures.

A classic example can be found in the food and beverage sector, where taste preferences can make or break a product. Consider a globally successful snack or beverage brand that introduced its signature flavor profiles to India without modifications. While the product may have been a hit in Europe or East Asia, the response among Indian consumers was lukewarm at best. Nielsen’s Global Consumer Confidence reports consistently show that Indian consumers are highly specific in their flavor preferences: they favor regional spice profiles, varying levels of sweetness, and textures that correspond to local culinary habits. What was perceived as “balanced” or “moderate” sweetness in one country might be seen as overly sugary or insipid in parts of India. Without tailoring taste to regional palates — or at least conducting granular preference testing across key cities and rural areas — brands miscalculate what Indian consumers actually want. In such cases, products end up on shelves, but without repeat purchases, which is the lifeblood of retail success.

Cultural resonance — or the lack thereof — further complicates the market. A product that succeeds due to cultural relevance in one market can fail spectacularly in another where the cultural context is entirely different. India’s consumption patterns are deeply influenced by traditions tied to festivals, rituals, and food habits that vary dramatically across states. A global dairy drink, for instance, might be positioned as a health supplement in Europe, whereas in India, dairy consumption is closely linked to daily staples like curd, milk tea, and traditional dairy-based sweets. Without embedding a product into the fabric of local consumption occasions — morning tea breaks, festival gifting, family meals — brands struggle to find relevant usage stories that Indian consumers identify with. Research by Euromonitor International highlights that products with strong cultural alignment demonstrate up to 3x higher repeat purchase ratescompared to those that rely solely on global brand equity.

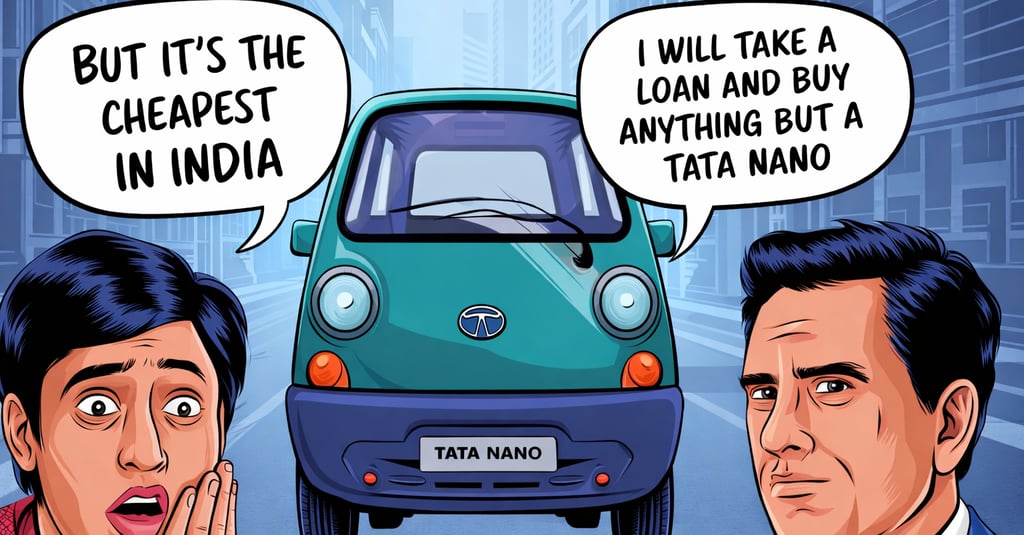

Pricing, too, emerges as a critical inflection point in the Indian context. India is one of the most price-sensitive consumer markets in the world. A study by Deloitte on Indian FMCG pricing dynamics found that over 60% of Indian consumers cite price and value-for-money as the primary decision factor, outweighing brand prestige or global origin. When global brands price products based on global benchmarks without accounting for India’s complex tax structures — including import duties, GST, and regional levies — the final retail price becomes prohibitively high for the majority of consumers. In such cases, even if the product is welcomed for its quality, it remains confined to niche urban pockets with limited purchase frequency. This scenario is particularly prominent in categories like nutraceuticals and premium personal care, where imported products are often priced significantly above local alternatives. Without tiered pricing strategies or affordable pack sizes, these products fail to convert trial into loyalty.

Usage mismatch is another dimension where global brands stumble. While a product may be technically excellent, its perceived utility in everyday life is what drives consumer adoption. A cosmetics brand that emphasizes a particular benefit — say, anti-aging properties — might succeed in markets where consumers prioritize that benefit, but in India, where day-to-day skincare routines are heavily influenced by climate, pollution levels, and traditional beauty practices, the same product may not intuitively fit into consumer behavior patterns. Market research by Mintel into Indian beauty trends reflects that Indian consumers often seek products tailored to humidity, sun exposure, and long wear in high-heat conditions. Without these localized product claims and performance assurances, even a globally lauded formula can be overlooked on crowded beauty counters.

The problem of misreading Indian consumers is not due to a lack of data; it is often a failure to interpret and apply that data appropriately. A Nielsen survey of Indian shopper behavior underscores the importance of localized insights: while global brands are recognized for quality, Indian consumers frequently choose local alternatives due to better contextual relevance and familiar usage narratives. A ready-to-drink health beverage imported from abroad might contain all the nutrients consumers want, yet if it doesn’t align with typical Indian consumption routines — such as morning tea or snack pairings — it will struggle to become a habitual purchase.

What this body of evidence points to is a deeper truth about consumption psychology in India: relevance trumps reputation. Indian consumers are pragmatic; they respect global quality but only reward it when it meaningfully enhances their daily lives in ways they understand and value. A product that fails to establish cultural and contextual relevance is effectively invisible, no matter how superior its technical attributes.

The cost of misreading these market realities is steep. International brands that fail to adapt often face sluggish shelf rotation, high distributor churn, and weak retailer support — all of which contribute to declining market share and, in many cases, eventual withdrawal. According to research by McKinsey India, brands that do not localize their offerings for Indian taste and usage patterns are up to three times more likely to underperform in their first two years of launch compared to brands that implement region-specific adaptations.

India’s consumer market is not an anomaly; it is a mosaic that demands strategic empathy — the ability to understand consumers not just as economic agents, but as cultural beings whose purchasing decisions are rooted in identity, habit, and context. For global brands seeking to win in India, the lesson is clear: build products with India in mind, not merely for India by default. Only when global excellence is married to local insight does a product transition from being technically excellent to consistently chosen by Indian consumers.

In the final analysis, brands that succeed in India do more than introduce a good product — they weave it into the fabric of Indian life. Those that fail treat India as another checkbox in their global rollout plans and pay the price when consumers simply do not see their products as part of their world. The story of great products killed by wrong market fit is not a cautionary footnote; it is a central chapter in the narrative of consumer globalization — and in India, it is a lesson that global brands can no longer afford to ignore.

Conclusion

India does not reject global products—it rejects irrelevance. The repeated failure of technically strong international brands in India underscores a simple but critical truth: consumer pull is created by cultural fit, not global reputation. When taste, pricing, usage occasions, and value perceptions are misaligned with local realities, even the most advanced products struggle to gain traction. India’s market rewards brands that invest in deep consumer understanding, local adaptation, and contextual storytelling. For global companies, success in India is not about importing excellence wholesale, but about re-engineering it through the lens of Indian consumers. Those who do so unlock scale and loyalty; those who don’t risk becoming another example of a great product lost to the wrong market.